Digital accessibility is about making sure that websites, apps, and digital content are usable by everyone, including people with disabilities.

Unfortunately, many organisations unknowingly make common mistakes that can create barriers for users. These mistakes can lead to frustration, exclusion and disappointment for users. In some cases, these barriers can also mean that public sector websites or mobile applications fail to meet their legal obligations. In the UK, The Public Sector Bodies (Websites and Mobile Applications) Accessibility Regulations 2018 require public sector websites and mobile applications meet the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.2 at AA standard and publish an accessibility statement that explains how accessible the website or mobile app is.

This post highlights 10 digital accessibility mistakes to avoid, along with simple workarounds to ensure your digital content is inclusive for as many users as possible.

1. Neglecting to use Alternative Text (Alt text) for images

Mistake: Failing to provide alt text for images (especially informative ones) means users relying on screen readers can't access the content or context of the image.

Solution: Always add descriptive alt text to all images, graphs, charts, and other non-text content. If the image is purely decorative, use empty alt text (for example, alt="") so screen readers can skip it.

GOV.UK guidance on images advises against using images alone to convey important information, as this can exclude users who cannot access the image. In such cases, leave the ‘Alt text’ field empty and provide a description in the body of the content to ensure accessibility for all users.

2. Poor colour contrast

Mistake: Using text and background colours with insufficient contrast can make it difficult for users with low vision or colour blindness to read your content.

Solution: Use a colour contrast checker, such as WebAIM: Contrast Checker, to ensure that your text meets a minimum contrast ratio of 4.5:1 against its background (WCAG 2.2. 1.4.3 Contrast (Minimum) (Level AA)), and that large text has a contrast ratio of at least 3:1. When selecting color schemes, take into account users with different types of colour blindness.

3. Not designing for keyboard navigation

Mistake: Websites and apps that require a mouse for navigation (or don't allow full interaction for keyboard users) exclude those who rely on keyboard-only navigation. Additionally, trapping keyboard-only users in an element without a way to escape using the keyboard further excludes this group.

Solution: Ensure your site is fully navigable using just a keyboard. Test tab navigation to make sure it moves through all interactive elements logically and to ensure that there are no keyboard traps on your website. You should also make sure that users can see what their keyboard is focused on at all times.

4. Ignoring semantic code or ARIA (Accessible Rich Internet Applications) roles

Mistake: Not using semantic HTML elements or ARIA roles, or using them incorrectly, can make it difficult for screen reader users to understand content and interact with complex elements like forms or interactive widgets.

Solution: Use semantic HTML elements (like <button>, <nav>, <header>, and <form>) wherever possible to ensure accessibility by default. When semantic code isn't enough, implement ARIA roles, properties, and states to enhance accessibility, ensuring elements like buttons, alerts, and navigation are correctly identified for screen readers.

5. Not providing text alternatives for videos

Mistake: Not providing captions or transcripts for videos excludes users who are deaf or hard of hearing. Additionally, users in noisy environments may struggle to follow videos without sound.

Solution: Always provide captions, subtitles, and transcripts for video content. Use platforms that support accessible video features, or embed captions manually for better accessibility.

6. Complex or unclear language

Mistake: Using jargon, complex sentence structures, or unclear instructions can alienate users with cognitive disabilities or those who are not familiar with technical language.

Solution: Write in plain language, breaking up text into short, simple sentences. Use clear headings and bulleted lists to organize information. Provide explanations for specialized terms when necessary. You can refer to the gov.uk style guide for helpful tips and guidance.

7. Skipping headings or using them incorrectly

Mistake: Skipping heading levels (for example, going from an heading 1 (<h1>) directly to an heading 3 (<h3>) or not using them at all can make it difficult for screen reader users to understand the page structure.

Solution: Use headings properly in a hierarchical order (<h1> to <h6>) to provide a logical, accessible structure. Headings should describe the content of each section clearly.

8. Unclear or missing form labels

Mistake: Forms that lack labels or use generic placeholders (like "Name" in the input field) make it difficult for screen reader users to understand what information is needed.

Solution: Always provide clear, descriptive labels for form fields. Use the <label> tag to associate text descriptions with form controls, and make sure they’re accessible via screen readers. Avoid relying solely on placeholders as labels.

9. Inaccessible pop-ups and dialog boxes

Mistake: Pop-ups and dialog boxes that don’t trap focus or offer an easy way to close can be disorienting for users, especially those relying on screen readers or keyboard navigation.

Solution: Ensure that pop-ups and modals are accessible by keeping focus within the modal and providing a clear, accessible way to close it (for example, a close button with a focusable escape action). Use aria-live regions to announce updates.

10. Failure to test for accessibility

Mistake: Not testing your site for accessibility issues means missing out on potential barriers that could affect users with disabilities. It’s easy to overlook mistakes without feedback from real users or automated tools.

Solution: Regularly test your site using automated accessibility tools and manual testing (including using assistive technologies). Also, conduct user testing with people who have disabilities to get real-world feedback.

Incorporating accessibility into your design process from the start not only helps you meet legal and ethical obligations but also creates a better experience for all users. Regular testing and ongoing education on accessibility best practices will help you stay compliant with the regulations and ensure your digital spaces are continuously improving to be inclusive for all users.

Remember:

- Test your content for accessibility

- Raise awareness about accessibility

- Build accessibility into your design from the start

- Test with real users to find issues

- Consider all users: Design for everyone

- Keep accessibility in check regularly

Helpful resources:

- Understanding accessibility requirements for public sector bodies

- GDS’s mobile app testing guidance

- Dos and don'ts on designing for accessibility

- iOS accessibility guidelines: Apple's official resources for developers

- Android accessibility guidelines: Google’s recommendations for making Android apps accessible

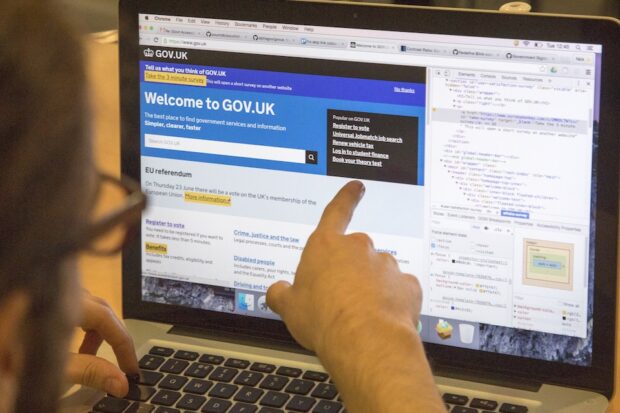

Any images in this blog post are courtesy of GDS.